- ill-defined (adj.)

- Posts

- artifice (n.)

artifice (n.)

on the frustrations of criticizing AI (so called)

Am I more concerned about artificial intelligence (a dubious phrase1 ) or annoyed that I am forced—as a creative, a writer, an editor by profession—to parse the hall-of-mirrors discourse erected around it by hypemongers and capitalists?

One of the most frustrating things about opposing AI (so called) as a layperson is its apparent slipperiness as a concept. What “is” it, exactly? Is it the harbinger of existential change or a harmless tool? Its proponents, always hedging on specifics, predictably attempt to steer that conversation in both directions, massaging fears and enthusiasms, respectively, in order to gain a tighter grip on the economic power they so transparently crave (to say nothing of their other, uglier aspirations2 ).

One low-hanging rhetorical handhold I’ve heard bandied about is that systems like Dall-E 2, Midjourney, ChatGPT, and their progeny—all built on large language models—are not actually “intelligent” (which is true), that they do not “think” (also true), that they are essentially sophisticated prediction and recombination machines (again, true). They do not know what they are making, lay critics say, and rightly so; they have no intention, no understanding. It’s true, treating ChatGPT as a search engine will yield entirely fabricated, if superficially convincing, results (case law research, for example). These systems are essentially the virtual equivalent of a very (very) large number of monkeys hitting keys at random until the result is something reasonably recognizable (with the help of a troubling amount of underpaid—and unpaid—labor behind the scenes).

There is an uncomfortable ambivalence to the intentionality argument, though, borne out of course by the nature of language, art and creativity itself. As literary theorists have been saying for decades (if not longer) intention is not the guarantor of meaning. ChatGPT churns out perfectly glossable—if in all ways soulless—text all day long. Midjourney and its graphical siblings are increasingly (frighteningly) adept at re(re)combining the imagery they scrape (without permission) off the internet into convincing visual coherence.

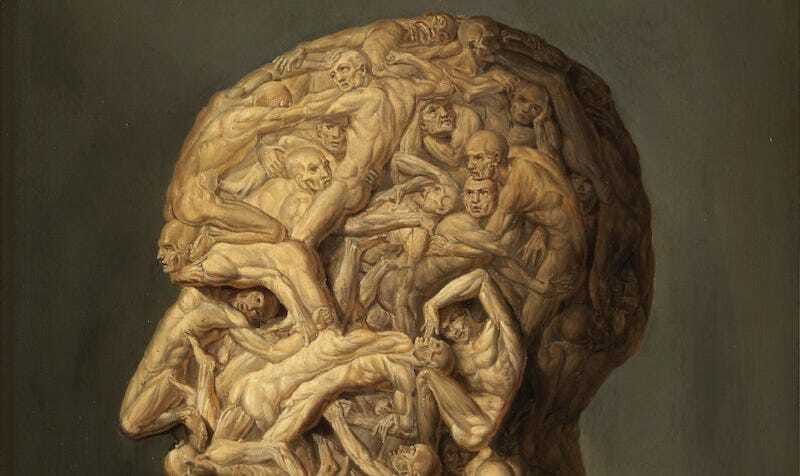

To argue, as some have, that AI (so called) does not create proper ““art”” because it merely synthesizes examples it has been fed by others is to flirt with damning all art, if we are to take seriously the insights of aesthetics, theory and philosophy. Of course, there are some hype men—presumably having lately disembarked from the NFT train scrounging for their next fix—who seem explicitly in favor of damning, if not art in general, then artists specifically. Which is why appeals to aesthetic judgment are insufficient; it isn’t (just) meaning that’s at stake, but human value itself.

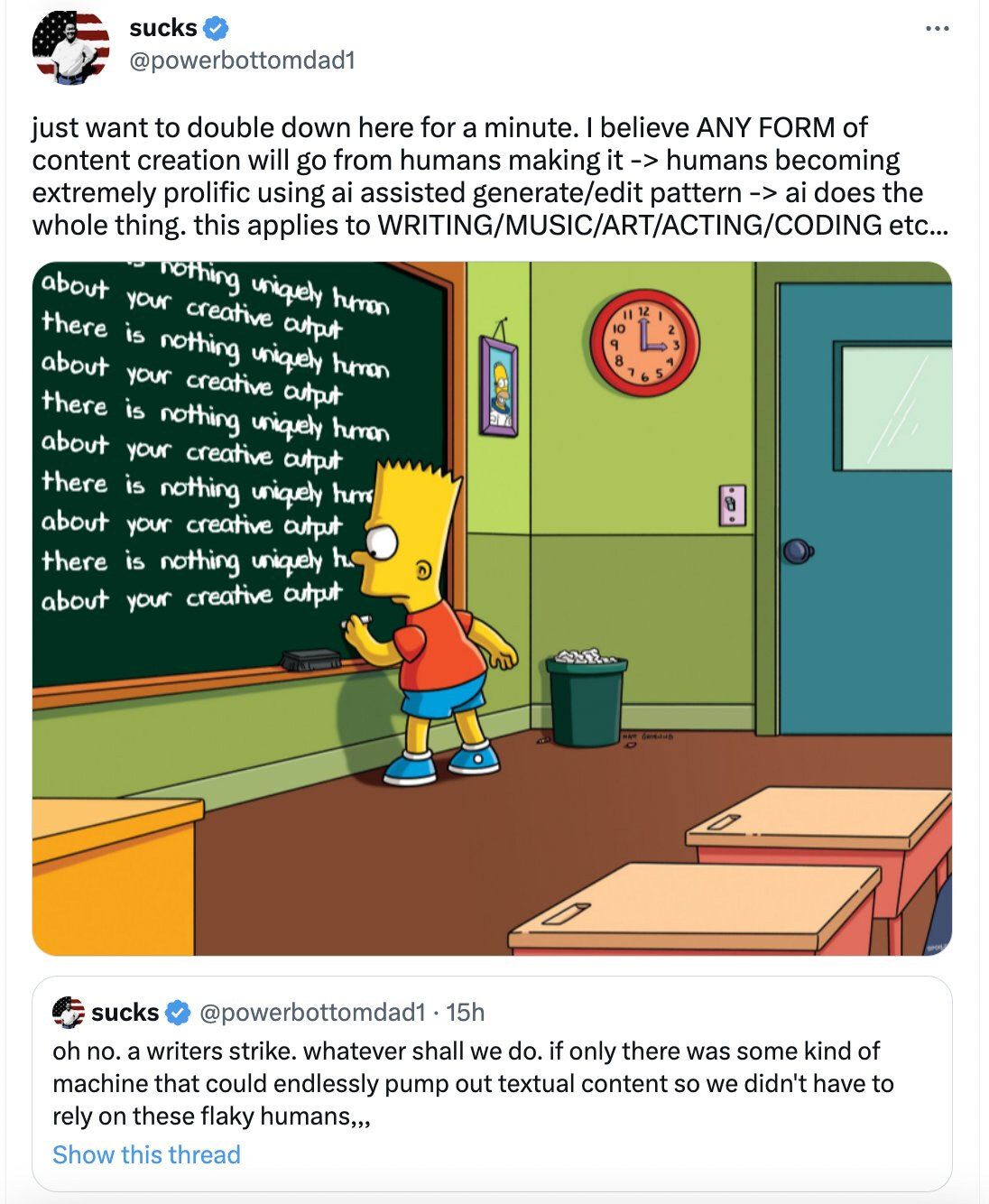

Accelerationist weirdos like @powerbottomdad1 who troll our timelines with visions of automating human artists out of existence merely parrot what the owners of AI (so called) profess. These technologies are not meaning-making machines but brute force bludgeons, accumulations of overwhelming processing power allowing their creators and proponents to flatter themselves by assailing human significance itself, as when Sam Altman, OpenAI’s venture capitalist CEO, declares humanity to be just as incognizant as his technology (“i am a stochastic parrot, and so r u”): a view of human life and labor seething with some of the glibbest nihilism a capitalist has ever frothed.

Ultimately, the trouble with AI (so called) is that it is both an appendage of and a diversion from exploitation: an assemblage, in the words of Dan McQuillan, “for automatising administrative violence and amplifying austerity” on the one hand and “a reality distortion field that obscures the underlying extractivism and diverts us into asking the wrong questions and worrying about the wrong things” on the other. As another group of writers has more concretely put it:

Many of these systems are developed by multinational corporations located in Silicon Valley, which have been consolidating power at a scale that … is likely unprecedented in human history. They are striving to create autonomous systems that can one day perform all of the tasks that people can do and more, without the required salaries, benefits or other costs associated with employing humans.

“AI” is not a technology but a convocation of software, narrative and political power, no one part existing independently of the others. It thus seems ever clearer that one cannot seriously criticize AI (so called) except by criticizing the exploitative structure of capitalism itself, which is why it seems much easier to many—including to me until recently—to take what seems like a moderate position, accepting, as McQuillan puts it, the pessimistic position that AI (so called) is in some way inevitable instead of admitting that its “social benefits are still speculative while the harms have been empirically demonstrated.”

1 “Our lack of self-consciousness in using, or consuming, language that takes machine intelligence for granted is not something that we have co-evolved in response to actual advances in computational sophistication of the kind that Turing, and others, anticipated. Rather it is something to which we have been compelled in large part through the marketing campaigns, and market control, of tech companies selling computing products whose novelty lies not in any kind of scientific discovery, but in the application of turbocharged processing power to the massive datasets that a yawning governance vacuum has allowed corporations to generate and/or extract. This is the kind of technology now sold under the umbrella term ‘artificial intelligence.’” Emily Tucker, “Artifice and Intelligence,” Tech Policy Press, March 17, 2022

2 “The structural injustices and supremacist perspectives layered into AI put it firmly on the path of eugenicist solutions to social problems.” Dan McQuillan, “We come to bury ChatGPT, not to praise it.” February 6, 2023