- ill-defined (adj.)

- Posts

- god (n.)

god (n.)

on The Mummy, Clive Barker's Next Testament, and the ambivalences of defeating God

The Mummy (1999) persists as one of my comfort films, though only partially for bisexual reasons; it also has to do with the pleasures of defeating God.

While Imhotep, the undead Egyptian priest and villain of the film, is ostensibly a mere man ritually cursed with eternal torment for having an affair with the pharaoh’s daughter, Anck-su-namun, he nevertheless consistently behaves and is portrayed in the style of a god. And not just any god: when he literally brings the biblical plagues down on Cairo, the drunk comic relief character, Jonathan, suddenly sobers and starts quoting relevant verses from the book of Exodus at the audience. Earlier, the awakened Imhotep stops short of killing the minor antagonist, Beni, when the scoundrel eventually prays his way through a collection of holy symbols until uttering Hebrew, at which point Imhotep withdraws. “The language of the slaves,” he says, conscripting Beni into his entourage. For a film about ancient Egyptian mythology, the writers have trouble seeing Egypt except through the lens of Jewish or, as is probably more apt, Christian interpretations.

Within the framework established by The Mummy, divinity seems to lie in the power to bring the dead to life. Yes, Imhotep can also control the desert sands and, as mentioned, bring down supernatural plagues of fire, pestilence and blood, but it’s his ability to call forth the dead to serve him with a word that makes him godlike. This isn’t a terrible rubric for divinity, seeing as it’s similar to the traditional Christian proof for the godhood of Jesus, “who was descended from David according to the flesh and was declared to be the Son of God … by his resurrection from the dead.”1 The difference between blessing and curse gets blurred beyond recognition when we (ridiculously, I know) compare these texts. The narrator of The Mummy explains that according to his “curse,” Imhotep “was to remain sealed inside his sarcophagus to be undead for all of eternity,” for if he were released, “he would arise a walking disease, a plague upon mankind, an unholy flesh-eater with the strength of ages, power over the sands, and the glory of invincibility.” For someone ostensibly “cursed,” the freed Imhotep seems to have a fabulous time wreaking havoc with what by all appearances is a kind of divinity. This is not a far cry from how the Apocalypse of John (a.k.a. Revelation) describes the returning Jesus, who eagerly unleashes supernatural destruction upon the earth in the pursuit of a kind of vengeance.2

I was returning to The Mummy (and Revelation) after reading Clive Barker and Mark Miller’s comic series Next Testament (2014-2015), another story about releasing and eventually thwarting God, and finding myself wishing it had been written by someone else—someone better read in apocalyptic literature and more familiar with apocalyptic Christianity.

Inversely to the ways in which The Mummy interprets ancient Egyptian history and religion crookedly, as it were, leaning on biblical texts in a way that underscores the film’s colonialist ambivalence, Next Testament riffs idiosyncratically on its religious themes3 with a breezy, charismatic, but often frustratingly inattentive approach to the source material responsible for making the narrative premise so interesting in the first place.

Of course, the main character of Next Testament is God, or rather, Wick, one of three supernatural beings behind creation. Wick calls himself “the Father of Colors,” the very god of creation, who fashioned humans in his own image in the beginning. A sort of flaming pansexual inverse of Alan Moore’s technicolor Dr. Manhattan, Wick is freed from an ancient stone prison somewhere in the desert by old hubristic rich white guy Julian Demond, who thenceforth becomes the god’s prophet-cum-lover as Wick tries to get up to speed on how his creation has progressed, the better to resume his lordship over it.

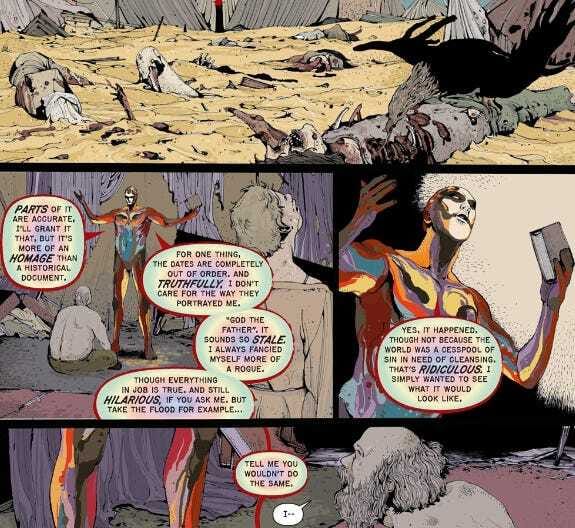

One of Wick’s first acts—after draining the life from Julian’s wife and exploding his entire dig crew into so many blood smears—is to read the Bible. As Wick tells Julian his side of the story, we get a clear picture of Wick as a pathologically dependent aesthete and hedonist on an order only omnipotence could produce:

“Take the flood for example… Yes. It happened. Though not because the world was a cesspool in need of cleansing. That’s ridiculous. I simply wanted to see what it would look like. Tell me you wouldn’t do the same.”

We learn that Wick’s brethren intervened upon his hedonistic dependency on humans to imprison him after the the incident with Abraham and Isaac:

“Abraham had promised me his undying love. But as soon as Isaac was born, there was no room left for me. He had to die. And I told Abraham as much. It was to be a sacrifice. How better to prove his loyalty to me? ‘Lay not thine hand upon the lad’...spake a different lord. The sacrifice was stopped. I was betrayed. My companions in eternity conspired against me.”

It’s ultimately these sibling deities who come to Earth’s aid in Next Testament’s climax, after the protagonists resort at last to pray to them in the moment all seems lost. But the struggle of atheists to deal with the literal existence of God(s) is honestly the least interesting thread of the story (and unfortunately, the one Barker and Miller seem most invested in). I rather find that the really compelling thing about Next Testament is how it takes literally the character of the God of Genesis (granting that Genesis’s multiple spliced source texts result in something of a split personality at times).

Wick’s need for worship comes from a place of emotional neediness verging on the infantile; and given that he is omnipotent, he hasn’t the least qualm in causing and threatening mass pain and death to get it. “When I am ready I will announce myself,” he tells Julian, “and the world will rejoice. It will have no other option.” At one point, Wick kills everyone in San Francisco (“insects”) when they begin to irritate him with their questions and complaints, muttering to himself, “I can always make new ones to play with. If I wanted to. I don’t need them. They need me.” (Very unsubtle, but when was Clive Barker subtle?) Wick, omnipotent but emotionally unfulfilled, has no sure way to trust that he could ever be loved by his creations, and so abuses his power to coerce a kind of fearful performance of respect out of them, which predictably only exacerbates his insecurities.

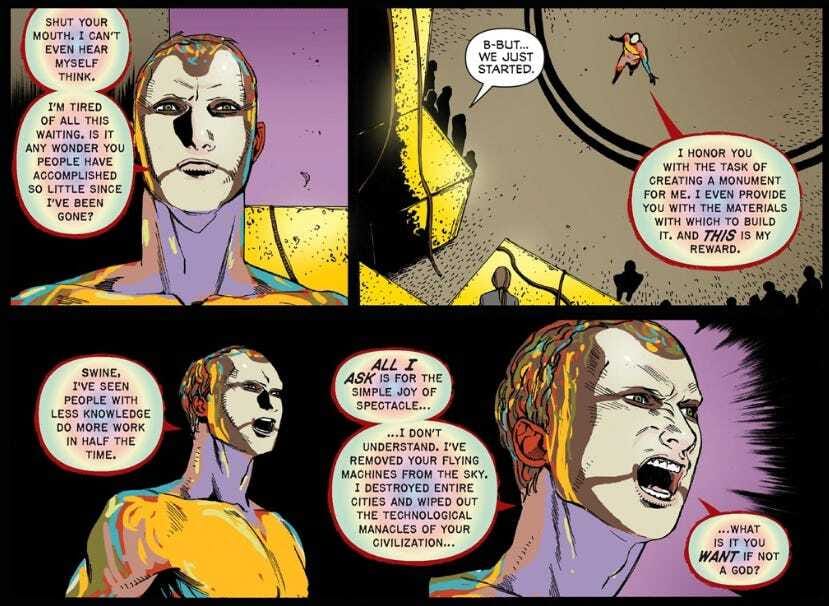

What gives Next Testament its dark humor is how sharply these tyrannical abuses fail to get him what he wants, which—in good conservative fashion—is a return to the way things used to be (“We must return to the old madness.”). For a god of creation, Wick’s attempts at getting the world’s attention tend toward mass destruction (tearing scoffers apart with his mind, crashing every airplane simultaneously, disabling mass communication channels, disappearing the entire American Midwest). When his demand for the construction of a massive pyramid is frustrated by the fact that the urbanites of San Francisco have no idea how to even go about such a thing, he complains:

“I don’t understand. I’ve removed your flying machines from the sky. I destroyed entire cities and wiped out the technological manacles of your civilization. What is it you want if not a god?”

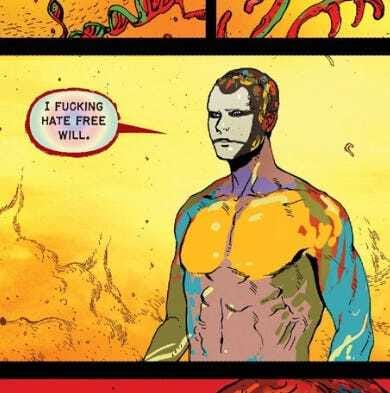

Summing up Wick’s insecurities as he threatens to end the world entirely, the climax consequently has my favorite line of the whole series:

To me though, Next Testament fails to cash out its concept in some important ways; and I feel like more familiarity with apocalyptic Christianity would’ve brought the story in a more compelling direction, or at least would’ve avoided, for example, the chapter in which a group of evangelical survivors kidnaps the protagonists and attempts to ritually execute them for… being nonbelievers, I guess?

This subplot shows off a condescending and simplistic interpretation of conservative Christians, casting them as necessarily benighted, backwater southerners (“Whut?”) taking the opportunity to inflict arbitrary violence for the grave sin of not believing. While apocalyptic evangelicalism is, in fact, despicable in a lot of meaningful ways, the sneering disdain on display in the writing overshoots plausibility in a way that actually undermines the rest of the story for me, recasting it as a sort of vulgar liberal atheist answer to Left Behind. Barker and Miller seem to think that theism itself is what lies behind far-right christo-fascist violence: a superficial and credulous reading of fundamentalism.

I grew up and became an adult in an apocalyptic white fundamentalist church, the product of successive schisms from its 1930s root, an organization I am often tempted to describe as a cult even though it always shared so much of its DNA with white evangelicalism more broadly. I believed for a long time, along with most of my friends and family, that a god not unlike Barker and Miller’s Wick would return one day to forcefully establish his kingdom on Earth. Every year in the fall, we rehearsed in sermon and song the coming destruction of our (see God’s) enemies, the decimation of the earth’s population from plagues and cosmic signs, a sobering but necessary intervention. Some of us believed we would be swept up in it, transformed into spirit beings as the literal “sons of God” just in time to join Jesus the warrior when he charged into Jerusalem; most took comfort from the fact that we’d be spared any direct participation in such widespread destruction. All of us looked forward to a time when every person on earth would be brought to heel under God’s benevolent dictatorship, his order enforced by supernatural surveillance and coercion (don’t do what he says? congratulations, your entire country gets to starve until you do!). A very “The world will rejoice. It will have no other option” kind of situation, come to think of it.

The appeal of this apocalypticism goes beyond simple dogma. It comes from a confirmation of feeling “chosen,” of being privileged with the right to one’s resentments and reassured that the most powerful being in the universe will one day (soon?) come to reward you for it by making you into something of a god yourself. The optimism of chosenness mingles treacherously with the best of what religion also offers, be it love or purpose or community. But underneath, white evangelicalism inflects all of this through the thick lens of fantasies about persecution leading to the vindication of the power it already possesses in a white supremacist society. Tad Delay puts it well in his analysis of the movement:

“Theological chosenness bleeds into racial or national chosenness like a manifest destiny. The chosen believer rests assured she’s a member not only of the true faith but the correct lifestyle, the blessed nation, and so on. Every other doctrine can and will be shown disposable.”4

However, as Delay goes on to point out, the upshot of this chosenness, bolstered as it is by fantasies of the second coming, is not necessarily direct violence but rather a state of being “completely free of and indifferent to the trauma of the world.” If my experience is anything to go by, white evangelicals writ large aren’t so much gunning to commit violence themselves as to see righteous (see shameless) violence committed on their behalf.

In any case, there is no such complexity in Next Testament, and I think it’s lesser for it, unfortunately. While attempting to use his omnipotence to try (re)building a “kingdom” for himself on Earth is very much in the vein of the over-the-top, alt-imperialistic god of Revelation, Wick and his story inexplicably stops short of the spectacular violence in which even that ancient book so enthusiastically indulges. And so Next Testament fails to represent how characters like the pastor and his congregants might convincingly respond to a situation in which according to their script they ought to be vindicated and empowered but are instead destroyed and forsaken the same as the unchosen by a god who simply can’t be bothered with doctrines or covenants (things Wick suggests resulted from the ham-fisted attempts of his brethren to manage creation in his absence).

I would’ve liked to see a story that, instead of taking the perspective of a handful of atheists, follows an evangelical, or even an ex-evangelical (a guy can dream, can’t he?), who has to reckon with the radically, violently unorthodox arrival of a god who is just as vindictive, arbitrary and insecure as the scriptures often portray: perhaps a story in which humanity does not prevail, in which this god is triumphant, in all his horrifying glory, and is not conveniently restrained in the final moments by gods more circumspect than he.5

Thank you for reading ill-defined. This post is public so feel free to share it.

1 Romans 1:3-4.

2 The personal, in the case of God, tending necessarily to inflate toward the global.

3 As expected for the minds behind a film like Hellraiser (1987).

4 Against: What Does the White Evangelical Want? (2019)

5 Maybe this yearning is coming from the fact that right before I read Next Testament, I finished Alan Moore’s magisterial Lovecraft trilogy (The Courtyard, Neonomicon, and Providence).